The Importance of Constant Innovation in Keeping a Business Ahead of Its Competition, and Thus Retaining Its Monopoly Power

Metallica is a great case study to support this argument

For many businesses, it is very important to constantly innovate to stay ahead of the competition, and a great example of such a company is Intel,1 which sold 60 million microprocessors for $21 billion in revenues ($5.2 billion in profits) in 1996 — up from 1986 with revenues of $1.27 billion and losses of $173 million.

So what happened?

In 1971, Intel created one of the first microprocessors, and got its big break in 1981 when it introduced its third-generation chip: the 8088. IBM chose to use this chip in its personal computers (PCs), but only if Intel agreed to second-sourcing: license its product to other manufacturers (e.g., AMD).

Unfortunately for Intel, AMD then dominated the market with Intel’s innovation!

So when Intel introduced its 386 chip in 1985, it refused to second source (and IBM agreed), thus allowing it to stay several steps ahead of competitors and their “clones” via regular upgrades, brand loyalty, and “switching costs”.

More specifically, whenever Intel’s competitors were legally able to “clone” Intel’s chip, Intel was already selling its new, more advanced chip, giving it an essential monopoly in the market for that new chip. By continuing to innovate in this way, Intel’s competitors were always running to catch up to something that was already becoming out of date.

A more fun example of such strategic competition is the band Metallica, and it will be the focus of today’s article. Whether you like this band or not, it is a great example of the importance of staying ahead of one’s competition by constantly innovating — sometimes to great success while other times attracting much criticism for allegedly “selling out”. Nonetheless, the band still remains a highly successful and influential act, which would not have been true if they chose to rest on their laurels.

But before beginning this issue of my newsletter, I want to note that what follows is heavily (no pun intended) based on three books that I highly recommend reading:

Brannigan, Paul and Ian Winwood (2014). Birth School Metallica Death: 1983-1991. London: Faber & Faber.

McIver, Joel (2009). Justice for All: The Truth About Metallica (Updated Edition). London: Omnibus Press.

Wall, Mick (2010). Enter Night: Metallica the Biography (Fully Updated with a New Epilogue). London: Orion.

Also, if you enjoy what I write and find it valuable, I request you consider a paid subscription to Walls and Bridges. It will help me to devote more time and other resources to write more and better articles for you in the future. Regardless, I am glad you are here!

The Monopolistic Competition Model

The early 1980s was a glorious time-period in which to live. It was when I saw my very first movie in a theatre: E.T. – The Extra Terrestrial. It was when my favourite TV show was The Incredible Hulk, which my parents incorrectly thought inspired me to smash the taillight of my brother’s pickup truck. And it was a time when some of the greatest music ever created was blasting on teenagers’ stereos: glam metal!

Ahh, glam metal: a form of music that was led by trailblazers like Mötley Crüe, Quiet Riot, Twisted Sister, and W.A.S.P. You might have heard it being denigrated by haters as “hair metal”, but what do they know? These bands took their inspiration from the likes of the Beatles, Rolling Stones, Led Zeppelin, The Sweet, Cheap Trick, Alice Cooper, Iggy Pop, New York Dolls, Ramones, and Sex Pistols, but then made a style of music like no other.

However, record executives like money, so the success of these bands motivated them to sign anyone that wore their sisters’ clothes and their mothers’ make-up, leading to lots of very similar bands like Faster Pussycat, Tora Tora, Danger Danger, Kix, Pretty Boy Floyd, Poison, Warrant and Kik Tracee. Now don’t get me wrong: I love some of these bands, but they were largely pale imitations of the legends. It got to the point where there was little money to be made with this kind of music, not only because the market became over-saturated with such bands, but also because the music-buying public was tiring of the superficial “sex, drugs, and rock & roll” mentality.

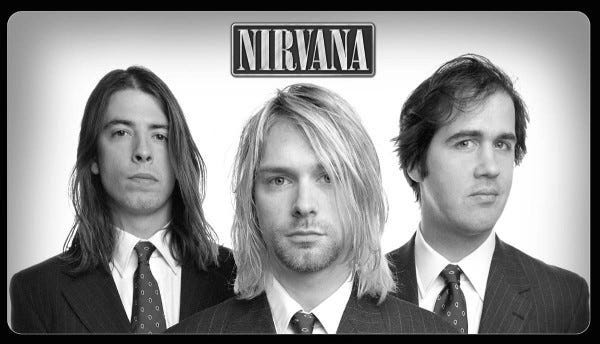

Which brings us to the genre known as “grunge”, led by seminal bands like Nirvana, Pearl Jam, Alice in Chains, Soundgarden, Mudhoney, Melvins, and Screaming Trees. They were new and exciting, and although they had many of the same influences as the glam bands, they were much less focused on image and more on using the brains in their heads rather than the ones in their pants.

But as with the glam bands, grunge was so popular that record executives demanded that anyone who dressed like they were homeless and feared showers were signed to labels. That led to many similar bands that were much less “authentic” in some people’s minds, like Candlebox, Bush, Live, and Collective Soul (again, I love these bands); it also led to other “post-grunge” bands like Nickelback, Creed, 3 Doors Down, and Puddle of Mudd.

Since then, there have been other trends that have arisen from the deaths of previous trends, like 90s pop-punk (Green Day, Offspring, Blink-182, Sum 41, etc.), nü metal (Slipknot, Korn, Limp Bizkit, Linkin Park, etc.), and emo (e.g., My Chemical Romance). But to my knowledge, there has never been another new worldwide rock/metal phenom in the mainstream since then.

Economically, it appears these music trends are consistent with a market structure economists call “monopolistic competition”. In such a market structure, the pioneering bands — such as Mötley Crüe for glam and Nirvana for grunge — are close to being monopolists in their style of music, because there are initially so few other bands like them; even the competition that does exist is differentiated in certain ways. Therefore, the trailblazers can make a butt-load of money, but not for long because entry into the market is so easy that clones quickly come into existence to compete for these profits. Eventually, there is so much competition that there is little-to-no money left to be made, and a new trend emerges.

Furthermore, as seen over the years, the movement from the top of the cycle to its bottom has grown increasingly rapid, as the Internet makes the entry of the clones all the easier. It has gotten to the point where the latest trend is almost literally “here today, gone tomorrow”.

However, the simple theory of monopolistic competition does not seem to entirely explain these music trends, because there are still musicians and bands that remain profitable long term, regardless of trends. One such example is Metallica, and the remainder of this issue will focus on applying this theory to the progression of their career. But first…

Was Metallica the First Thrash Metal Band?

Prior to Metallica forming in the early 1980s, there were very few bands resembling what later became called “thrash metal”, but they did exist. As Joel McIver argues in his chapter titled “The Truth About Thrash Metal”, Metallica were not the absolute first thrash metal band, and their album, Kill ‘Em All was not the first thrash album.

He argues European thrash metal was advanced early by three bands: Venom, Mercyful Fate, and Bathory. He especially gives credit to Venom and their second album, Black Metal, released in 1982 (one year before Kill ‘Em All). While there are disagreements on the influence (and talent) of Venom, their is broad agreement that while the speed of thrash came from that band, and its lyrical and production rawness come from the punk scene, Motörhead single-handedly inspired all “extreme metal” with their attitude alone — although Motörhead’s leader, Lemmy thought this idea of his influence is “ridiculous”.

But the true originator of “thrash metal” is irrelevant for our purposes. What matters is that prior to Metallica, the dominant musical genres were not nearly as fast and heavy as bands like Venom, Motörhead, and Metallica; more importantly, Metallica were the primary band to turn “thrash metal” into a more dominant genre. By the same token, Nirvana was not the first “grunge” band — as bands like the Melvins came first — but the Nevermind album was the one that led this genre to skyrocket in the music industry.

The Beginning of the Thrash Metal Cycle and Kill ‘Em All

To explain the rise of thrash metal in terms of the monopolistic competition model, other dominant forms of music in the late 1970s and early 1980s were coming to an end in terms of popularity, and thus in terms of profitability for music executives. For example, disco music was quite popular during these years, but the market became so over-saturated that even bands with a harder edge were putting out albums that were disco influenced, including Blondie (“Heart of Glass”), Kiss (Dynasty and its lead single “I Was Made for Loving You”), the Rolling Stones (Some Girls), and Alice Cooper (From the Inside). Thankfully, disco died.

Similarly, there was “yacht rock”: soft rock which dominated FM radio in the late 70s and early 80s. Again, this market became over-saturated and the record-buying youth sought out new and exciting music that was more influenced by punk and hard rock bands from earlier years. Two such genres were glam metal — started by bands discussed above — and thrash metal (the origins of which were explained earlier).

Even though Metallica did not literally start thrash with Kill ‘Em All, they were the primary reason why the cycle for thrash began in the first place. In other words, as argued by Brannigan and Winwood, Kill ‘Em All was not particularly heavy by today’s standards, but it did help set the benchmark for where the genre would progress.

However, the thrash metal movement did not start with a bang: just as the grunge movement took time to reach a mass audience — even in terms of Nirvana, since Nevermind was their second album — Metallica did not create a worldwide sensation with Kill ‘Em All. To be certain, there was a lot of excitement in the underground metal scene, but that was pretty much it, so record labels were not even interested in signing them; according to Jon Zazula — quoted by Brannigan and Winwood — the label executives laughed in his face when he tried to get Metallica signed, so he decided to form his own independent label called Megaforce to release the album.

Nonetheless, Metallica kept pushing forward, opening for Raven on their first proper U.S. tour, called the “Kill ‘Em All for One” tour, named by combining the name of Metallica’s album with Raven’s All for One album title. Brannigan and Winwood quote Raven lead vocalist John Gallagher as saying Lars had a “stick of dynamite up his arse”, and that he was “the mover and shaker” who “asked 20,000 questions.” The other members of the band, however, were “very Californian”, as James was shy and barely said two words, Kirk seemed happy to just be on this adventure, and Cliff was “the epitome of cool”.

In fact, Raven were mentors to Metallica, for example by helping them learn how to convert rowdy audiences to fans. Specifically, Ulrich was surprised that Raven was able to take a very tough and scary crowd and have them dancing on tables in the end. When asked how they did that, Gallagher told him, “Well, we believe in what we do. Don’t you believe in what you do? And [if you do] then why don’t you go up there and show them?”

Long story short, while Metallica did not start a new monopolistically competitive cycle right away, they were working toward that goal. As Brannigan and Winwood argue, “In 1983… Metallica were pioneering Earth-shifters constructing a road that for all they knew may well have led to nowhere.”

Staying on Top with Innovation: Ride the Lightning

If Metallica were content with putting out the same kind of album over and over again, then they might have eventually had a bit of success, but it would not have created some kind of monster like we know today. They probably would have gone on for some time and then fallen by the wayside like so many other bands that simply rode the prevailing wave, including the glam bands.

So what did Metallica do that was special? Like many other long-term successful businesses, they innovated: while other thrash bands who remained “true to their roots” and eventually disappeared, Metallica updated their style in a way that kept them at the top of their cycle.

Recorded in Copenhagen with producer Flemming Rasmussen, Brannigan and Winwood argue correctly that the material on their second album, Ride the Lightning, “stood years rather than months ahead of” songs on Kill ‘Em All. They were largely helped by both Burton and Hammett, the latter having essentially no input into their first album given the fact that he arrived just in time to record it. Cliff studied music at college and was influenced by Bach and Beethoven, in addition to ZZ Top and the Misfits, so he was able to contribute unique input into the new songs. According to Lars, the band was no longer a “one-dimensional musical unit”.

Similarly, Brannigan and Winwood quote European tour manager, Gem Howard:

…bands that tend to come through are the ones who are listening to stuff that isn’t necessarily what you’d expect them to listen to. If you go out with a very average British thrash metal band, all they tend to listen to is thrash metal; so all of their influences come from the same kind of music that they are making. There’s nothing new in there. But with Metallica, at one minute they’d be singing along to the Misfits, while the next minute they’d almost be crying their eyes out listening to “Homeward Bound” by Simon & Garfunkle.

Lars Ulrich knew that to be the biggest band in the world, they needed talent, discipline, and grift, according to Brannigan and Winwood. In addition to the influences Burton brought into the recording studio, Kirk Hammett was committed to mastering his instrument as an end in itself, rather than just to be famous. He was also not a ticking timebomb like Dave Mustaine. As for James Hetfield, he no longer could rely on Mustaine to be the leader on stage, so he became a much stronger stage presence, while also growing to be a better lead guitarist and lyricist.

In terms of specific songs on the Ride the Lightning album, Brannigan and Winwood give further evidence of Metallica using innovative approaches to music that not only kept them at the top of their cycle, but which also motivated clones. For example:

In 1984 this acoustic-then-electric technique displayed on ‘Fight Fire with Fire’ was sufficiently revolutionary and effective as to be quickly seized upon by thrash metal’s chasing pack and copied to such an extent that within two yeas it would be rendered a cliché.

Also, the authors argue “The Call of Ktulu” is “a piece that owes as much to nineteenth-century European classical music as it does 1980s European heavy metal.” Moreover, “Fade to Black”, which was written by James while mourning the theft of their equipment before a Boston gig, was their first ballad, but it created both costs and benefits for the band: it cost them some fans who cried “sell outs!” but it also attracted a new and wider audience who liked the song, particularly females who wrote many of the 300 letters per week to their fan club ran by K.J. Doughton.

Given the increased attention the album generated from the music-buying public, Metallica were able to sign an eight-album deal with Elektra Records, although they did not inform Jonny Z of his fact in advance. Zazula was upset, but he agreed to pass over the rights to the album after selling 75,000 units under the Megaforce label, and he eventually conceded that the band only went in this direction because they felt it was best for their career.

The band then signed a management deal with Cliff Burnstein and Peter Mensch of Q Prime, the management of Def Leppard who were on top of the world with Pyromania selling 7 million units in the U.S. alone. According to Brannigan and Winwood:

Burnstein was struck by the impression made by a band who ‘while only being twenty-one or twenty-two years old’ were in possession ‘of a pretty goddamned good idea of what they wanted’: not only that but had learned from experience ‘how some things can go bad because [a manager] doesn’t have enough money…

Lars said rather prophetically:

Cliff Burnstein who signed us to our new management deal in the States has this big belief that what we are doing will be the next best thing in heavy metal — especially in the States which is something like 80 per cent of the market — and this whole Ratt, Mötley Crüe, Quiet Riot, Black ‘N Blue thing will get kinda old and die out, and that Metallica will lead the way in a sort of new “true metal” trend… I’m not saying it’s something that’s going to happen overnight, but it could start developing and Metallica could be the front runners of a new branch of heavy metal.

The band continued to become more successful from there. For example, the Megaforce edition of the album entered the Billboard charts with more than 30,000 copies sold on the independent label — a major accomplishment. They also got their first cover story, this being in Kerrang! Then their final live show in 1984 was at the Lyceum in London, at the time a Mecca-owned ballroom, more than five times the capacity of the Marquee — this despite only being played on Radio 1’s late night Friday Rock Show.

Metallica went on to a successful tour in the U.S. in 1985 with W.A.S.P. and Armored Saint, influencing metal music to become heavier. They were then booked on the Monsters of Rock festival at Donington, headlined by Rainbow, with performances by Scorpions and Saxon. Two weeks later, they performed on the first day of the Day on the Green festival headlined by Scorpions, and also including Ratt, Y&T, Yngwie Malmsteen’s Rising Force, and Victory. Metallica was actually the only group on the first day of the festival to grow after that date. The rest declined in significance.

Then the band proceeded to record what many consider to be their greatest album (and also the greatest album in all of thrash metal), Master of Puppets.

Master of Puppets and the “Thrash” Label

Once again, Metallica continued to remain at the top of their monopolistically-competitive cycle by being increasingly innovative, which in no small part involved Hetfield and Ulrich being more open to Burton’s contributions in terms of harmony and melody, and thus being more experimental

Bringing back Flemming Rasmussen as producer, and ultimately going back to Copenhagen to record the album, the significant improvement in the band’s technical abilities were noted not only by Flemming, who said they were obviously much better in terms of technical abilities (especially Lars), but also by legends that they respected, including Geezer Butler of Black Sabbath, K.K. Downing and Glenn Tipton of Judas Priest, and Iron Maiden manager Rod Smallwood, all of whom were treated to a listening of rough mixes by a drunken Lars Ulrich after he and Hetfield ran into them at the Cat & Fiddle in Los Angeles.

As argued by Brannigan and Winwood:

…with their third album Metallica would light a fuse that would burn a slow but determined path towards a charge of such force that it would change the sound and nature of metal’s mainstream forever.

Despite no singles or exposure on MTV, the album entered the British Gallup Album Chart at #41, and reached #29 on the Billboard Top 2000 Album Chart in its first month. It also got rave reviews in the music press, and the band were honoured to open for Ozzy Osbourne on his Ultimate Sin tour. This is the album many believe made Metallica the “Kings of Thrash”.

But is that an accurate assessment? Slayer released their best album, Reign in Blood, the same year, and they recorded it in an attempt to beat Metallica in terms of speed and heaviness, so perhaps they could rightly be called “thrash metal”. However, Lars had no problem with any of it because he did not even like that label, believing it to be constricting and complaining about being “pigeon-holed”. He also stated:

From a musician’s point of view, I don’t really like that term… It implies lack of arrangement, lack of ability, lack of songwriting, lack of any form of intelligence. There’s a lot more to our songs than just thrashing.

In that light, Brannigan and Winwood argue that as with Nirvana and grunge, Metallica came from thrash but were never quite part of thrash.

Furthermore, the “Big 4” thrash metal bands were always very different in style and substance. As explained by Joel McIver, Slayer were best known for being faster than all of its contemporaries, with twin lead guitars and ungodly fast drumming, along with (initially) a Satanic gimmick. Anthrax were much less inclined to frown, growl and walk around in all black clothing than its contemporaries. They were also less concerned with mock-horror and more into comic books, Stephen King novels, and skateboard culture, not to mention being the first to incorporate rap & hip-hop into heavy metal music with their Public Enemy collaborations. As for Dave Mustaine’s post-Metallica band Megadeth, they were much more technically proficient than other “thrash” bands, with some people calling them “technical thrash”.

Whether one wants to lump all of these bands into the “thrash” category, the application of the monopolistic competition model to these bands is appropriate: they are all similar but different enough that if none of them ever innovated in their styles, eventually there would be so many “copy-cat” bands that fans would eventually lose interest in them and the genre would be dead-as-disco. Although all four of these bands have had periods in which they either took a break or risked disappearing altogether, their willingness to innovate their styles while (usually) remaining true to themselves have made them highly successful all these decades later.

Closing Remarks

Not every attempt by Metallica to start a new cycle was successful — such as the Load and Reload albums in the 1990s, and St. Anger in the 2000s, although those albums have become more appreciated in recent years — but the point is that to remain at the top, a band/business needs to adapt to changing markets while still remaining true to it primary vision.

Thank you for reading to the end, and I hope to see you all here again next Monday!

Source of this Intel example: Church, Jeffrey and Roger Ware (2000). Industrial Organization: A Strategic Approach. Toronto: McGraw-Hill, pp. 111-12.